tl;drThe routing problem:

- IBC tags assets based on the sequence of IBC channels they have been transferred over, so the same asset transferred over two different paths will have two different denoms

- Usually, there’s only 1 “correct” (i.e. highly liquid) version of each asset on each chain (and frequently there are none)

- Sending assets to their origin chain

- Find the shortest path from the origin chain to the destination chain, and using the most liquid path when there are multiple distinct shortest paths.

- Plus, staying flexible to unusual exceptions

Routing Problem

IBC Tokens Get Their Names & Identities from Their Paths

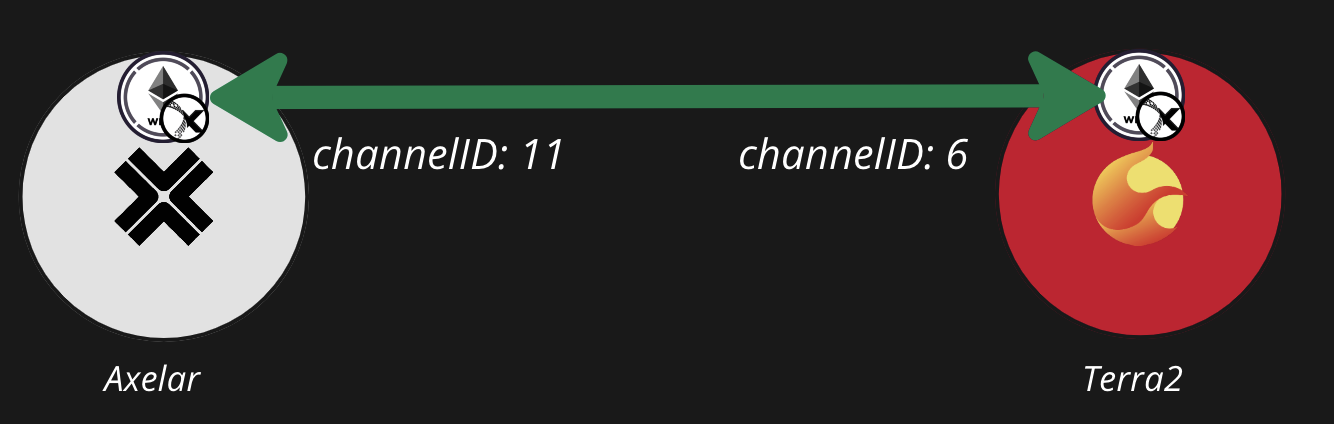

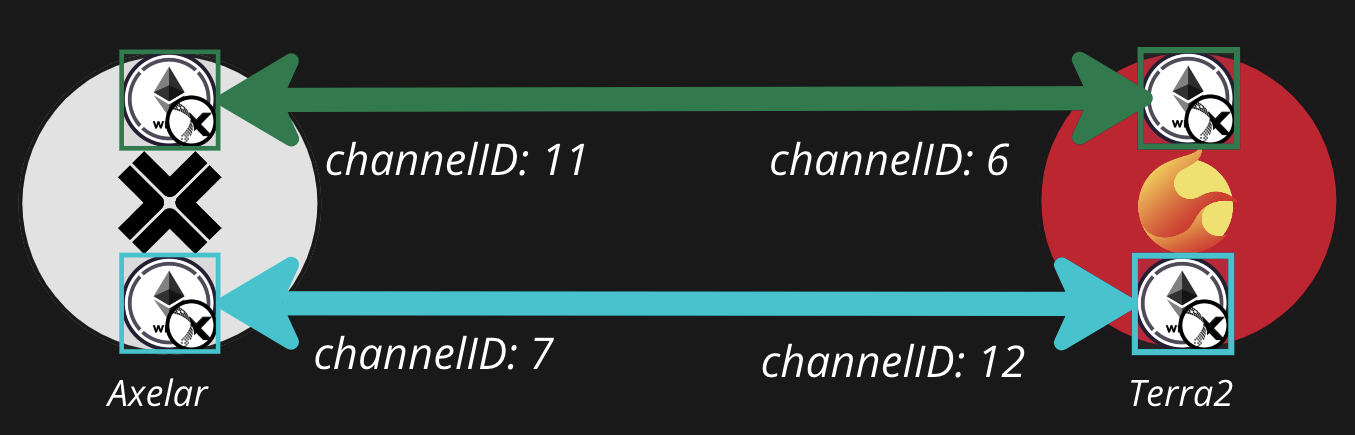

IBC transfers data over “channels” that connect two chains. Channels are identified by human-readable port names (e.g. “transfer”) and channel IDs (e.g. channel-1). For example, consider a transfer channel between Terra2 and Axelar:

Naming Algorithm

hash is typically the sha256 hash function

Continuing the example from above, the denom of this version of WETH.axl on Terra2 is:

axlWETH on Terra2

So Different Paths Produce Different Tokens

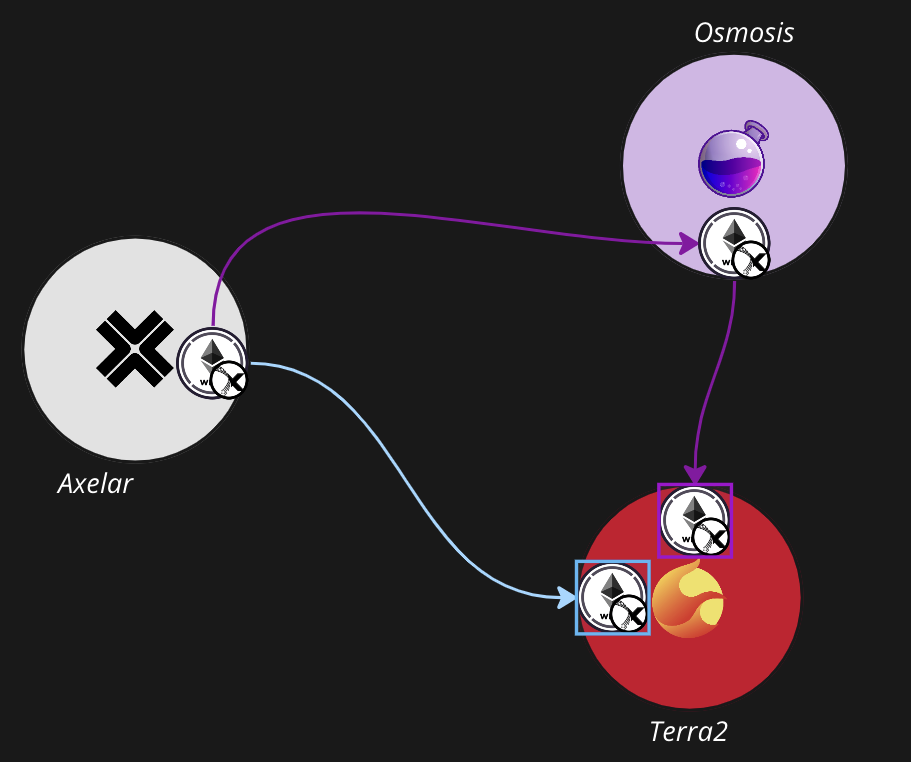

Now that you understand that IBC denoms get their names from their paths, you understand the crux of the routing problem: The same asset transferred to the same destination over two different paths will have different denominations. Continuing the example from above, WETH.axl transferred directly from Axelar to Terra2 will have a different denom than WETH.axl transferred through Osmosis:

There are many paths between two chains, but usually only 1 useful version of each asset

Right now, there are about 70 IBC-enabled chains. At least one channel exists between almost every pair in this set. This dense graph of channels contains a very large number of different paths between almost any two chains, which creates many opportunities for “token winding” or “mis-pathing”, where a user sends an asset through a suboptimal path of channels from one chain to another and ends up with an illiquid / unusable version of their token. Mis-pathing almost always produces a practically useless + illiquid version of their token on the destination chain because there’s usually only 1 useful version of a given asset on a given destination chain (if that). (There are over 50 versions of ATOM on JUNO!) As a result, we need to be very careful to send the user through the correct sequence of channels. The next section explains our token routing algorithm.Routing Algorithm

Insight about routing: The correct route depends on the chains + the asset in questionNotice that the correct route for a particular asset A on a particular chain Chain-1 to another chain Chain-2 depends not only on the channels that exist between chain-1 and chain-2, but also on what asset-A is.This is because asset A is defined by its path from its origin. Consider the following two cases:

- If asset-A is native to Chain-1, perhaps it can be routed directly over a channel to Chain-2. This would yield a simple asset given by path of Chain-1->Chain-2

- If asset-A originated on another chain (e.g. Chain-3), it’s very unlikely that transferring directly over a channel to Chain-2 would give the correct version of asset A on Chain-2. This would yield a more complex denom given by path of Chain-3->Chain-1->Chain-2, which is probably wrong if Chain-3 and Chain-2 are directly connected.

- Instead, the asset should probably be routed back through the channel that connects Chain-1 to Chain-3 first, then sent over the channel to Chain-2. This yields a path of Chain-1->Chain-3->Chain-2, and a final denom given by the path Chain-3->Chain-2

- Route the given asset back to origin chain (i.e. “unwind” it)

- Check whether any high-priority manual overrides exist for the given asset on the given destination chain. If so, recommend the path from the source that produces this high-priority version of the asset

- If no high priority manual overrides exist:

- If at least 1 single-hop path to the destination chain exists (i.e. if origin chain and destination chain are directly connected over IBC), recommend the most liquid direct path.

- If no direct path exists (or if the client on the direct path is expired, or none of the asset has been transferred over the direct path), do not recommend any asset

- We run nodes for every supported chain to ensure we always have low-latency access to high quality data

- We index client + channel status of every channel + client on all the chains we support every couple of hours to ensure we never recommend a path that relayers have abandoned or forgotten about.

- We index the liquidity of every token transferred over every channel on every Cosmos chain every few hours to ensure our liquidity data is up to date. And we closely monitor anomalous, short-term liquidity movements to prevent attacks